After examining the evidence and spending much time in denial, Andy eventually accepted the truth: he was an accident. Unwanted. A fluke. He wasn’t meant to exist, and his existence caused more strife and annoyance in the lives of his family members than his nonexistence would have. It would’ve been much easier for his parents had he not been born, not to mention much more pleasant for his sisters. He was thankful that up to this point, they’d done a decent job at pretending Andy was meant to be here. Yet he wondered if they should’ve been upfront with him from the beginning. You should know, we didn’t plan on you being here. Would that have made things easier now? Or worse before?

Once this conclusion about his birth—that he was simply a twist of fate—was reached, thirteen years into Andy’s accidental life, he fell deeply into the dark hole that was I-Should-Have-Known. Really, it was amazing he’d made it so far without realizing. He remembered, when he was younger, going to playdates and being exposed to so many new things, modern things, that he didn’t have at home: remote-controlled cars; Hot Wheels that transformed into cyborgs that spoke in deep, garbled, electronic voices; Nerf guns that shot foam bullets at the speed of light; Go-Karts with neon green flames splashed along the sides. All Andy had to offer when his friends came over was Lincoln Logs, Twister, and chalk. They were hand-me-downs, his parents explained, refusing to buy him whatever the spoiled brats he spent time with were using these days. If it’s not broken, why fix it? Your sisters loved these when they were your age. If Andy was as snarky as his playmates, he would’ve snapped back, I’m not a girl and that was like twenty years ago.

Which led him to another hint. Another clue that his family was meant to be four, not five. When Andy was born, his twin sisters were eight. Of course this was ideal as Andy was growing up – Amelia and Tessa fawned over him as if he were their own child, cuddling him and pushing him around in the Dora the Explorer stroller and dressing him up in outfits they’d designed themselves. However, once Andy reached the age when he could govern his own body, they didn’t find him as adorable. He was now the annoying little brother. Andy’s friends experienced this too, but while Amelia and Tessa downright ignored Andy, his friends’ sisters fought with them. It’s probably because we’re basically the same age, one friend noted, and Andy, for the first time, realized that it wasn’t normal among his peers to have siblings that were eight years older or younger. Amelia and Tessa reached high school before Andy reached middle school. It didn’t help that his sisters looked like their father while Andy looked like their mother. One friend joked that in a few years people would start thinking that Andy’s sisters were his mom. He shuddered in horror at that.

It was obvious, or it should have been. The clues were everywhere. Andy’s bedroom walls were painted pink because when he was born, Tessa had to move out of his room and into Amelia’s to share. The aunts and uncles and grandparents seemed to forget he existed, hugging his sisters with gusto at family gatherings and then, like an afterthought, giving Andy’s hair a friendly ruffle. Professional family photos weren’t taken until Andy was nine – until then, only pictures of his parents and sisters were hung around the house, no Andy to be seen.

Andy tried to remember what he thought about all these things before the truth dawned on him. He couldn’t remember feeling anything; yet now, knowing, he felt a little lost. He figured he should’ve felt angry or sad, but in the place of some extravagant emotion there was only numbness. One thing was for certain: he couldn’t look at his parents or his sisters the same way again. He knew they loved him. His parents were better at showing it, but all four of them seemed content that Andy was alive. But he wasn’t supposed to be! He found himself wondering what life would be like for the four of them if he wasn’t around, which only made him feel more uncomfortable, but it was a sensation that refused to go away now that the knowledge was wedged in his brain.

It was after a botched Facetime call with his sisters when the seed was planted. He was in bed, watching a fishing video that his best friend Brant had sent him, when his parents called him downstairs. Amelia and Tessa, away at college and remaining there for the upcoming summer, had finally found time in their busy schedules to meet up and call home. His parents were ecstatic. They huddled side-by-side next to the island, closer than Andy had seen them in forever, his father holding the phone at arm’s length so his daughters could see both their parents fully from the waist up.

“Geez, Dad,” Andy mumbled, leaning on the island a few paces away. “They can see you, you don’t have to show your whole body.”

“Come say hi, Andy,” said his mother, not bothering to look at him as she wiggled her fingers at the screen. “Hello hello!”

The service was bad at the house – it always was – and the twins’ voices cut out like they were standing outside during an earthquake. Andy’s father brought the phone closer and he and his wife studied the pixelated faces on the screen, repeatedly insisting WE CAN’T HEAR YOU. I THINK THE CONNECTION’S BAD. HONEY, WE CAN’T HEAR ANYTHING YOU’RE SAYING.

Andy sighed and snatched the phone from his father. He pressed the red button.

“Andy?” cried his father. “What are you doing?”

“It’s not going to work. The Internet sucks. Just go to the computer room maybe and try again.”

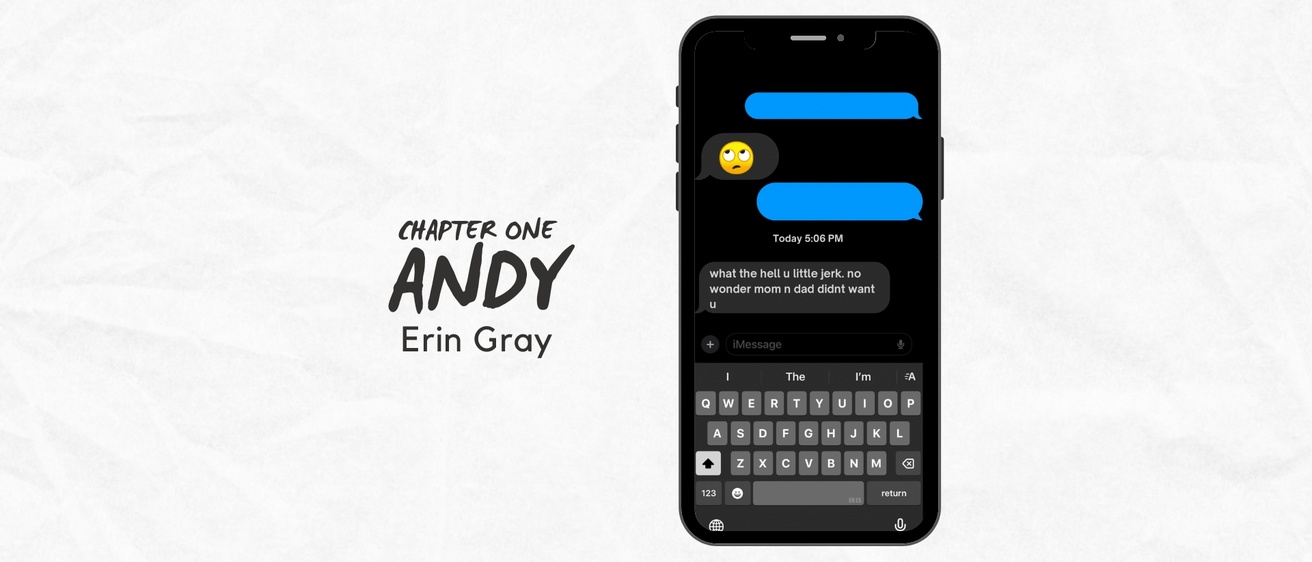

Upset but unwilling to ignore what could be useful advice, his parents sighed and obeyed. Andy retreated to his room to find a text from Tessa waiting: what the hell u little jerk. no wonder mom n dad didnt want u.

Andy sat on the bed motionless, his eyes glued to the screen. He knew well that over the years, cracks had begun to show in the twins’ once solitary, indistinguishable personality. Brant liked to say that Amelia grew up and Tessa grew down. The former became more responsible, more put-together, more level-headed; the latter grew more spiteful, more ignorant, more unreachable. Amelia tolerated Andy; Tessa hated him. He wasn’t unused to these types of messages from Tessa, often accompanied by the eye-rolling emoji or the yellow middle finger. But he’d never read a sentence quite like this one. What did she mean? It was obviously sent to get a rise out of him, but why would she say . . . that?

He leaned back slowly against the pink wall, took a screenshot, and sent the text to Brant with the caption: Miss Sunshine is in a good mood today!!! But he had ulterior motives in letting Brant in on the exchange, and just as he expected, Brant read deeper and replied: oh shit.

Brant didn’t curse often – he knew Andy wasn’t allowed to, so he tried to keep his own foul language to a minimum. When he did let a word slip, it usually meant something serious.

What

do you know why she said that

Yeah because I hung up the phone on her when she was talking to my parents

no like that specifically

? What do you mean lol

By now Andy was still playing dumb, but an uneasy feeling whirled a cyclone in his gut, and he considered running to the bathroom. He curled his legs underneath his body instead, set down the phone, wiped his sweaty hands on the bedspread, and picked the phone back up. Three bubbles bounced ominously on the screen.

andy if I tell you something do you promise not to freak out

Oh boy what did you do

no about her text

Uhhh ok I guess so

you promise

I promise

The news that Andy was an accident didn’t hit him as hard as Brant probably expected it to. Andy wasn’t necessarily in denial from the start; it just didn’t make sense. He thought he was decently smart, and you find something like that out pretty early if you’re an observant kid. It was like he was willing to accept that it was true but still somewhat believed that it was a joke.

Brant asked if he wanted to hang out – it was summertime, only a few days from June, and the two of them had planned to do something every day. School had ended a few weeks ago and they’d already ridden their bikes on every street in town (twice), completed the most difficult level in their favorite video game as of late (just hours after school let out), and learned how to dive at the town pool (though cannonballs off the diving board were more fun, so they’d quickly gone back to those once they each dove correctly). It was early – Andy hadn’t had lunch yet because his mother was too busy scheduling and attempting to carry out the Facetime call to make something – but surprisingly, he didn’t feel like hanging out. Brant asked if he was mad (don’t shoot the messenger man I mean I’m sorry you had to hear it from me but like everybody knows. like that’s what my mom says) and he answered that he wasn’t (No it’s fine they probably told me a while ago and I just forgot and didn’t think about it). He wasn’t mad, that was true, but the thought of spending time with his friend just wasn’t ideal at that moment. His friend, a middle child, and therefore definitely not an accident.

Andy heard his parents speaking loudly in the computer room a floor below him, and he felt the tornado wreak havoc through his stomach again. They were probably going to blame each other for the bad connection, project the issue onto each other, and go back to the weird state they were in in which they couldn’t stand to be closer than five feet from each other. Andy wished, to his surprise, that his sisters were home. Then at least his parents could be around people they actually wanted to be around.

The three of them weren’t in a room together again until a week later, the night before Andy’s mother was setting off to Africa for work – he’d forgotten what country, for she was always traveling, and over time he grew to not care. She insisted that they have a home-cooked “family” dinner before her departure. Surprisingly, she’d made pot pies, Andy’s father’s favorite. Andy couldn’t remember the last time she had done something like that.

They were only a few bites in, the only sound in the dining room the metallic clatter of fork and dish. Andy said, “When were you guys going to tell me I was an accident?”

Andy’s father looked at his wife; she didn’t return his gaze. Instead, she stared at Andy in a kind of humored disbelief, her fork hovering inches from her mouth. Finally, she replied: “Where’d you hear that?”

“I just figured it out.”

“Did you,” she said thoughtfully.

When it became clear that was all she was going to say, Andy’s father spoke up. “That’s not a term we’ve ever used,” he said. “You weren’t an accident, Andy, we just didn’t expect to have you. Accident has such a negative connotation.”

Andy expected more – rather, he wanted more. There was no affection, no protectiveness in their tones. Shouldn’t they be tripping over their words trying to explain to him that even though he wasn’t supposed to be here, they were so thankful that he was? He remembered something Brant had texted: that’s what my mom says. The fact that other families felt more open and comfortable discussing Andy’s mistakeness than his own felt odd.

He didn’t know how to reply to his father, so he didn’t reply at all, and his mother seemed to have moved on from the subject as well. They went back to their pot pies, and the only thing spoken the rest of the meal was Andy’s father asking when his wife’s flight left the next day. Andy suddenly felt bad about declining Brant’s offer to hang out – they hadn’t seen each other since the discovery – and as soon as the table was cleared, he hopped on his bike and took off without a goodbye. If anything, the conversation taught him that he’d rather spend his time with people who weren’t disappointed in his existence.

About the Author

I started reading and writing as a child, and both have evolved together for me; I tend to write parallel to what I read. As a writer, my attention to detail is strongest in my characters, which is why I am drawn to writing a family saga. This chapter is part of a family saga that I am working on. I plan to explore each member of the family: Andy, his twin sisters, and his parents. Each will have multiple sections in closed third person. I do not have a clear path to follow for the work yet, so I cannot speak to the larger themes besides the strains among families as its members grow up, encounter challenges, and change, and how these things affect the different generations.

Instagram Account

@eringray21

Cover design made using Canva design tools.